(Scott A. Gavorsky, Ph.D.) – It is always odd when one of your personal interests suddenly becomes important to others.

I started this series in part to examine census data as it became available and how it related to policy decisions. A number of you have been along for the ride—thank you, dear readers! But I always imagined it would be a little niche project on the internet.

Even my 775 Alive podcast co-host had to be dragged kicking and screaming . . . well, sipping at least . . . into doing a Census podcast just recently (you can watch our “Citizenship and Census” episode here).

I can not say that it is a personal predilection anymore.

The Census has blown up in the last two weeks in ways I could not have imagined.

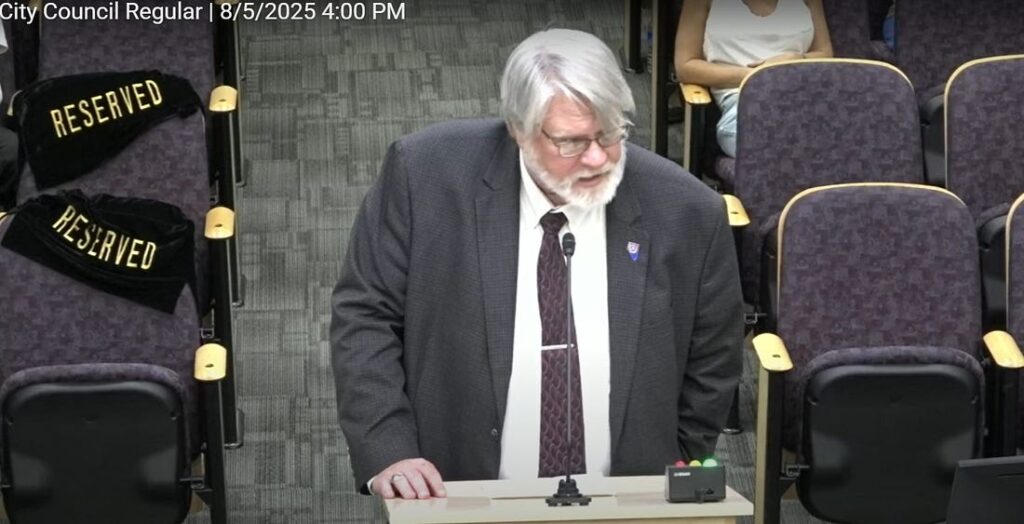

On a local level, I was retained by one of the parties in the dispute in Henderson’s proposed ward redistricting to compare the city-generated population estimates to Census Bureau data.

At the heart of the matter was whether the data showed sufficient population change between city wards to justify redistricting or if the redistricting was politically motivated.

The issue generated considerable controversy in the Las Vegas press and concluded with a very tense exchange between members of the Henderson City Council. I might share some more of my take on the episode in the future, after some reflection.

But while that was happening locally, two big national stories broke that touched on exactly the same issues as the Henderson case.

The Texas redistricting plan has threatened to launch a “redistricting war” across the country.

The redistricting apparently was undertaken at the request of the White House to increase Republican margins in the House of Representatives, under ongoing litigation stemming from illegal majority-minority districts in the 2021 redistricting.

As Texas moves forward, Democratic governors are claiming they are going to do mid-term redistrictings to reduce Republican seats in some vainglorious effort to “keep the balance” in the House of Representatives.

Is it too soon to point out a similar Congressional balancing policy as embedded in the Missouri Compromise (1820) and the Compromise of 1850 to maintain the number of free and slave states in the Senate was an absolute disaster?

But the new map also takes into account some significant growth in Texas since the 2020 Census that indicates more population is concentrating in the more conservative Dallas-Fort Worth area than the more liberal Houston.

It will be interesting to see if Democratic states that have been losing population are going to incorporate new population estimates into their redistricting efforts.

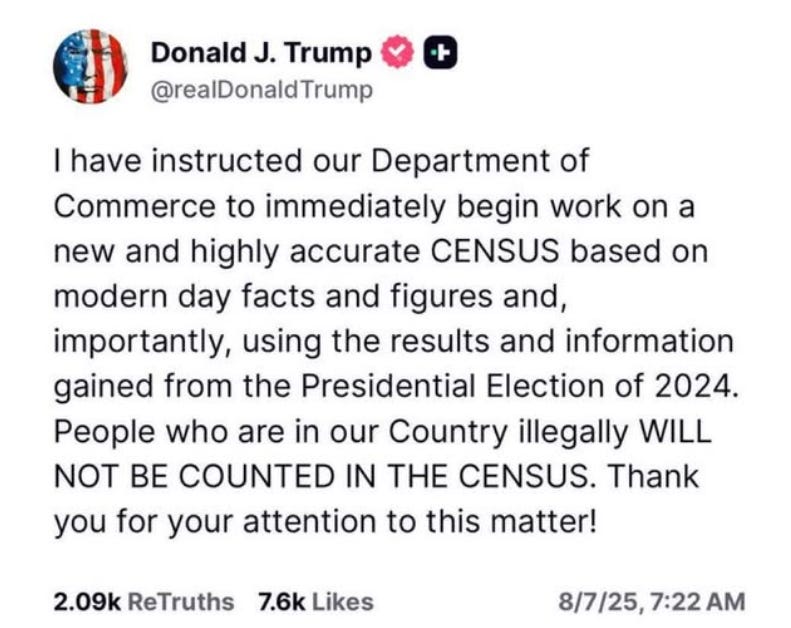

Finally, President Trump’s August 7th announcement ordering a “new and highly accurate Census” has thrown even more fuel on the fire.

In addition to the usual claim that people here illegally will not be counted (more on that below), two other interesting points are called for: the use of “modern day facts and figures” and the odd reference to “information gained from the Presidential Election of 2024.”

Truth Social post by President Trump announcing the order for a “new” Census on 7 August 2025.

Part of this appears to be the belief that the 2020 Census undercounted the population in six states and overcounted the population in eight (“America Counts” story, 19 May 2022).

The fact that these states were largely divided by political leanings—red states undercounted, blue states overcounted—was not unnoticed by many commentators, particularly by Hans A. von Spakovsky of the Heritage Foundation.

Spakovsky’s conclusion that it may have cost the Republicans five House seats seems to have been widely accepted by this administration.

The alternative sources of information are more intriguing for me. I am not sure how the 2024 Presidential Election data can be used for redistricting.

I suppose one could draw up a crude relationship between people who voted and the total population that might, somehow, relate to the number of illegals or migratory change.

Given the variables, I would consider such an approach next to useless.

The Trump Administration has spoken in favor of more use of “administrative data” in the Census.

These records—residency permits, change of addresses, and so forth—are capable of tracking some changes in the 10 years between the decennials. The administration also believes that administrative data can be used to identify illegals more readily.

But these administrative sources are not controlled by the Census Bureau, who in turn may not be able to verify the accuracy of the sources.

They also often include privacy-protected and even proprietary data (such as utility accounts) that are not subject to public scrutiny.

The use of similar data, generated by the city under guidelines established by the Nevada State Demographer, was one of the issues raised with the Henderson redistricting proposal.

What all of these have in common is that people are losing trust in the data used for redistricting, either the decennial Census or the new estimate approaches being proposed. Is there a way forward to resolve this debate?

Direct Counts versus Estimates

When counting populations, the decennial Census conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau remains the best direct count, the “accurate Enumeration” required by the U.S. Constitution, available.

Certainly, there have been some serious errors at times in the 23 Census counts since 1790, but on average, it has been the gold standard data set globally.

But there is one major problem with the decennial Census that is increasingly causing issues, however. It only occurs once every 10 years.

Modern Americans are moving far more readily and rapidly than they have in the past, especially since the end of the COVID pandemic. Many states and municipalities are finding themselves in a losing battle.

The increase in estimates for public planning is a direct result of this issue.

I have spent numerous articles looking at the Census Bureau’s two primary estimate programs, the American Community Survey (ACS) and the Population Estimates Program (PEP), which both attempt to provide intercensal data using two different methodologies.

The PEP relies on administrative data to produce estimates and, therefore, is a bit closer to what is currently being discussed by the Commerce Department. The ACS and PEP both give reliably consistent data, even if varying from the decennial Census count.

But they present real issues. Most significantly, the release schedule is slow.

The 2024 data, for instance, was just released in May 2025 for the PEP and will be released in September 2025 for the ACS—but only for large urban areas. Rural areas have to depend on even more dated information.

States have increasingly stepped into the gap by devising their own estimate programs to bridge these gaps. In most cases, these rely on local administrative data to produce estimates.

The programs in Nevada are largely based on practices from the State Demographer’s Office and tied closely to the distribution of the Consolidated Tax (the C-Tax).

The assumption is that if the estimates are good enough for tax distribution, they are good enough for redistricting.

My issue with that is no tax agency is going to issue tax refunds based on estimated data.

They will demand individual or household data—a direct count, in other words. The question is should we be asking the same for voting?

Should Estimates Be Used to Redistrict?

The discrepancies between direct counts of population (as in the decennial Census) and estimates (whether they are generated by the Census Bureau, the state, cities, tribes, et cetra) raise real questions of accuracy and precision.

In short, what is the best data that can be used for redistricting?

An important caveat is in order.

Saying an estimate is not valid for a particular use is not the same as saying that the estimate is wrong. And it leads too readily to charges that the reason the numbers are off is malfeasance of the enumerator.

Estimates can provide vital information in the right situation, but not all situations.

Let me provide a very simplistic policy debate that illustrates how multiple datasets can be correct but not applicable for various policy decisions.

On a certain residential street where kids play, there is growing concern about speeding cars. Three separate policy approaches are attempted.

1. A parent decides by personal experience but no data that cars are going too fast. They get one of those “Slow Down” stand-up turtles to encourage people to slow down and perhaps begin talking to neighbors about the issue.

2. The local city council responds to a growing number of written complaints, some sworn and some not, that cars are speeding down the road. They decide to approve building speed bumps at crosswalks to slow traffic down.

3. The city police respond to the same complaints by patrolling and issuing tickets to speeders on the road. This directly addresses individuals speeding and provides better data for a policy discussion.

Note that none of these datasets are “incorrect” in the sense of being right or wrong. But the information can not be used the same way.

A city council is not going to approve speed bumps based on a single parent’s complaint; they would not see it as proof of need. But multiple, consistent complaints can indicate a problem that needs to be addressed—even if the exact statistical extent of the problem is not clear.

But likewise, a police department that tried to issue tickets based solely on the complaints the city council acted upon would quickly find itself in legal trouble. Even a large number of speeding complaints is not the same as the proof of a radar gun needed to justify an individual ticket. Estimates of average car speed is not evidence.

These varying datasets are similar to the Census debates we are having today.

Many people have a sense something is off—whether it be non-citizens or population growth. Governments have some good estimates of the problem based on a range of administrative and statistical data—for example, comparing home occupancy permits with average family size.

But these are always subject to some inaccuracies.

What is needed for proper redistricting is a way to directly tie information—particularly citizenship, age, race and ethnicity for Voting Rights Act concerns, location—directly to voters.

If I can press the example above, accurate redistricting would require the police issuing tickets to really devised effective policy. And that means embracing the expense, the logistics, and the legalities needed.

In short, a direct count is what is needed.

A Census before 2030?

So where does this leave the country with President Trump’s announcement?

I remain in the camp that no new Census is going to happen before 2030. There simply is not enough time to conduct a new Census, either legally or logistically.

From the legal perspective, Title XIII of the U.S. Code that governs the Census has a pretty clear set of timelines. Topics to be covered on the decennial Census need to be approved by Congress three years before, and the specific questions approved two years before.

This issue is exactly what President Trump ran into in the 2019 lawsuit—it was simply too late to add the citizenship question. I doubt the administration will win any lawsuits with enough time to do anything before the 2026 midterms.

The question of not counting non-citizens towards apportionment for the House is on even shakier ground.

The Constitution, both in Article I, section 2 and the Fourteenth Amendment, section 2 are rather clear it is all persons that are to be counted.

A constitutional amendment would probably need to be passed to change the requirement.

On the logistical side, a decennial Census requires an enormous mobilization of personnel and resources—the largest such federal mobilization short of war, often close to 500,000 people.

It also normally requires years of planning—usually starting about 5 years out. This is one reason I think President Trump’s announcement is more theater than threat; now would be the time to organize the next Census anyway. He just seized the opportunity to add his two-cents-worth.

Some alternative theories are going around about a Census before 2026.

There is a lot of talk that if direct counts are needed, the “obvious” way to do it is to have the U.S. Post Office employees do the Census. They visit every home, right? Easy-peasy.

Except the Post Office does not work this way.

Many communities in rural Nevada and other areas do not receive direct home postal delivery. Efforts to reduce Post Office expenditures since the early 2000s have resulted in many rural residents required to have P.O. Boxes and pick up their mail at a central location.

Places like McDermitt, Wells, or many other rural locations would have to find the physical addresses, bring on additional staff to reach them, who then have to be trained to conduct the Census (just as their urban delivery counterparts will have to be).

If you are going to do all that, what is the difference logistically from another Census?

My take is that President Trump’s order is a clever warning shot more than an direct order for action.

A “new” Census does not by grammatical necessity mean an “additional” Census. It can mean a “changed” or “updated” Census, using new techniques and new methodologies.

It may mean more use of administrative data, which the Commerce Department (which manages the Census Bureau) is now implying. I imagine the pushback on that will be strong indeed, as it should be.

I have mentioned that we live in a data-rich world. The problem is that so much data exists that the arguments are drifting from identifying the best data to finding the data that meets a specific purpose.

And that raises the question of whether we can find common ground in the data we use.

If the administrative data that the Trump Commerce Department or the state of Texas is wrong for federal redistricting in areas of 750,000 people, why is the use of similar data acceptable for small precincts of 5,000 people, where the data is likely more inaccurate?

How should we solve the issues of population shifts that are now happening faster than every 10 years?

Or how to count people who are here illegally and may not want to be counted?

At the end of the day, all of these issues will need to be discussed. And now—five years out—is the time to have these talks.

The opinions expressed by contributors are their own and do not necessarily represent the views of Nevada News & Views.