German statist ideologies, Bismarck’s personal hostility to laissez-faire liberal ideas of free development, played big role

(Steven Miller of NPRI) – During the early 20th Century, in every American state save Texas, politicians and politically active special interests — some ostensibly representing labor and others business — passed into law compulsory systems of industrial insurance.

Moreover, even in Texas, longstanding common-law principles of liability and individual responsibility were overturned.

While these new compulsory state social-insurance systems offered advantages to some employers and some employees, all members of both groups were deprived of certain rights that formerly had been considered inalienable.

What had facilitated such a fundamental repudiation of longstanding American principles? It was the conjunction of a recently emerged “progressive” consensus with an opportunity for its imposition: a perceived crisis of widely reported industrial injuries.

The German infatuation

Neither the consensus nor the “crisis” was quite what it seemed. The former — a growing fatigue with laissez-faire liberalism that had been accelerating toward the end of the 19thCentury — was the flip side of a rising enthusiasm for Prussian-style schemes to use the centralized state as an engine to drive compulsory “reforms.” Following militarist Prussia’s swift victory over France in the Franco-Prussian war, imperial-minded Americans increasingly admired the Bismarckian state.

German statist ideologies also titillated certain disaffected 19th Century U.S. elites. The American Economic Association, for example, explicitly parroted Hegel’s doctrine that “The state is the actuality of the ethical Idea” when it founded itself, in 1884, upon a platform declaring:

We regard the state as an educational and ethical agency whose positive aid is an indispensable condition of human progress.

It was that very year that also saw the legislative birth in Prussia of state-mandated workers’ compensation.

As known today in the U.S., however, that traditional answer to the problem of injured workers is beset by multiple and growing challenges. On the one hand, as documented by ProPublica and others, the benefits for injured workers supposedly available from the workers’ comp “grand bargain” have for decades been shrinking — raising the issue of whether what remains, especially in certain states, is even constitutionally sound.

At the same time, “opt-out” alternatives arguably superior to traditional workers’ comp — seen from the standpoints of both employees and employers — have emerged in Texas, Oklahoma and Tennessee.

These alternatives, in many ways, reconsider and re-answer the original questions asked during the original birth pangs of workers’ compensation in 19th Century Prussia.

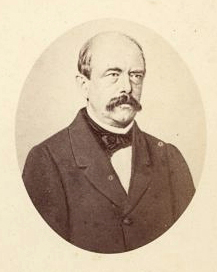

Bismarck in 1863, one year after assuming the Prussian chancellorship. Photo taken by the Italian photographer Alessandro Pavia.

Often romanticized today and attributed to the good will and progressive instincts of the chancellor and minister-president of Prussia (and Germany) at the time, Otto von Bismarck, the actual reality was significantly less ideal. John M. Kleeberg — whose deeply researched inquiry into the historical particulars behind the 1884 law was published by the New York University Journal of International Law & Politics in 2004 — concluded:

Social insurance did not arise from the moral benevolence of Otto von Bismarck, but from the crude horse-trading known to us from public choice theory.

Moreover, even beyond its political-horse-trading origins, American workers’ comp bears the marks, still today, of Bismarck’s personal involvement in its passage. If not for his own financial self-dealing, his well-documented deceitfulness and his obsession with ensuring absolute power for the feudalistic Prussian monarchy — which he dominated — the entire history of industrial insurance in the Western world could well have turned out very differently.

The perceived crisis

Prussia, in the early years of the Industrial Revolution, was a natural place for the issue of industrial injuries to first gain prominence. That state had, at the time, the most built-out railroad mileage of any country in the world.

The extent of the railroads in Prussia reflected that state’s grant of its powers of eminent domain to railroad firms, in which the state itself was also often a large investor. The Prussian monarchy — for centuries occupied by kaisers who saw themselves as military leaders first — saw railroads in terms of their utility, in case of war, for quickly moving armies.

Similarly well-developed in Prussia for that era was the mining of iron and coal — also fostered by the state.

While these “new industries actually may have been safer than the old agricultural economy,” notes Kleeberg, “what was new … was the mass accident and the publicity it engendered.”

To read the entire story, click here.

NPRI is a nonprofit, nonpartisan think tank that produces and shares ideas and information that empowers people. For more information, please visit www.NPRI.org.

Facebook

Twitter

Pinterest

RSS