Mark Halperin is not a household name unless you’re an “insider” dwelling in the DC Swamp. For those who have a life, Halperin is a former political analyst for MSNBC – which canned him in October after “at least a dozen” women accused him of workplace sexual misconduct.

Eve Fairbanks is not one of the women. She moved to DC in 2005 to become a reporter at the same time Halperin, as she put it, “ran a chummy daily political newsletter, The Note, from his perch as political director of ABC News.” And last week Fairbanks wrote a column, “We’ll Be Paying For Mark Halperin’s Sins For Years To Come,” detailing her experience covering politics in the nation’s capital and why she left.

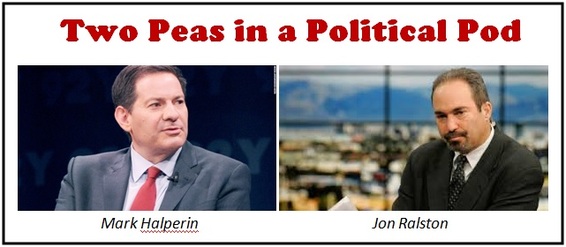

What’s extraordinary about the column – to me anyway – isn’t why and how Ms. Fairbanks became so disillusioned, but how closely her experiences in DC with Halperin mirror the longtime situation we suffer from here in Nevada with one of Halperin’s mini-me’s…Jon Ralston.

In fact, I’m going to rewrite Ms. Fairbank’s column below, only substituting Ralston’s name for Halperin’s, Carson City for Washington, the Ralston Reports newsletter for The Note, and a few other minor edits that don’t change the overall substance of the message – like substituting Democrat Nevada Senate Majority Leader Aaron Ford for Democrat U.S. Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer.

Those who have been involved in Nevada politics for the last decade or so will immediately recognize the amazing similarities to Ms. Fairbanks’ story.

So let’s pretend a fictional cub reporter who started covering Nevada politics in the mid-2000’s wrote the following column about her experiences before bolting Carson City for greener pastures…

* * * *

I want to talk about the deeper, subtler, more insidious effect Jon Ralston has had on our politics – one which we’ll be paying for for years to come.

Ralston Reports purports to reveal Carson City’s secrets. In fact, its purpose is the exact opposite: to make the city, and Nevada politics, appear impossible to understand. It replaces normal words with jargon. It coined the phrase “Gang of 63” (and reports on) the clubby network of lobbyists, aides, pols, and hangers-on who supposedly, like the Vatican’s cardinals, secretly run Carson City. That isn’t true – power is so diffuse. But Ralston claims he knows so much more than we do, and we begin to believe it.

Once you believe that, it’s not hard to be convinced that politics is only comprehensible, like nuclear science, to a select few. There are those chosen ones – the people who flatter Ralston to get a friendly mention in his newsletter, the ones he declares to be in the know – and the rest of us. Ralston writes about Carson City like it is an intriguing game, the kind that masked aristocrats played to entertain themselves at 19th-century parties: Everyone is both pawn and player, engaged in a set of arcane maneuvers to win an empty jackpot that ultimately means nothing of true importance.

At the same time, Ralston Reports makes it seem that tiny events – a cough at a press conference, a hush-hush convo between Aaron Ford and Michael Roberson in a corridor – hold apocalyptic importance. Cloaked in seriousness, in reality Ralston Reports is not news but simple gossip.

Gossip: The word comes from the old English for “baptismal sponsor” – a godparent – and Ralston positions himself as the priest who stands between the layman and the sacred mysteries of Carson City, only letting a person through in exchange for the corrupting coin of accepting your own personal idiocy. It requires acknowledging, like a cult initiate, that you have to learn the Master’s arcane knowledge before claiming to know anything at all.

Ralston Reports is a cult. Between bits of knowledge in each email, Ralston inserts birthday wishes to his gang, cementing the impression of Carson City as a place where people are much more interested in buttering each other up than they are in the lives of the kind of Nevadans whose names Jon Ralston does not know.

We have apocalyptic politics in part because Ralston helps promote an apocalyptic approach to political coverage. It makes him and his little scoops seem hugely important: that conversation he overheard between Roberson and Ford mean everything!

Politics for Ralston is a game and its rules are constantly being transformed. Ralston Reports’ intentionally hyperbolic, breathless text present details like the fact that Sandoval “woke up late and went for a coffee with his pal Pete Ernaut” the way an ancient monarch’s courtiers used to examine his every sigh for divine omens.

People often attribute our contemporary sense of perpetual crisis to social media, as scrolling newsfeeds monopolize our attention. But Ralston set this bar for news in Nevada before Twitter and Facebook took over the media. His endless drumbeat of meaningless micro-scoops helped create the impression we were living at the edge of time, where the present is as momentous as anything that has ever occurred. The future, in this context, cannot take any time or energy to be properly imagined.

It was Ralston who drove me out of Carson City a decade ago. For the three self-conscious and self-flagellating years I worked there, I felt absolutely convinced I could say nothing of insight about the city, and thus about politics or Nevada life, unless I scored a rare invite to the politico-socialite Heather Murren’s dinner party at Adele’s. I thought insight was merely about access – about being able to immediately recognize whose initials were referred to in the top paragraph of that morning’s Ralston Reports.

Thus I shelved the freshest, most original thoughts and impressions I had about politics and logged weeks angling for an interview with the right aide, or an invite to the right party, both of which invariably left me feeling like I still hadn’t scored the juiciest tidbit of info. Always the bridesmaid, never the bride. I felt powerless, a hopeless bumbler and hick by dint of my own lack of cool at Incline Village dinners.

As the Ralston ethos spread, it corrupted or destroyed nearly every Nevada media property that encountered it. I worked at the Reno Tribune-Gazette (fictional). We were never going to compete with Ralston’s insider access, and we were never meant to. But he fostered a monopolar atmosphere in which the one marker of success at political writing was to beat Ralston Reports.

I remember thinking: This is not really news! This is not like Watergate or My Lai, where if a dogged reporter doesn’t out the truth, it will never be known. The only scoop was to beat the other racers to the finish line, perhaps by minutes, in getting the name up on our website.

This helped create a media environment where we shot from the hip in an effort to get everything out as fast as possible – and because we were on the web, we rebranded all the inevitable mistakes born of way-too-hasty work as “updates” instead of “corrections.” No wonder the media is so distrusted. We spent frantic days massaging sources to try to beat Ralston. We were like dogs slavering after a piece of meat, but we weren’t in the wild eating for survival: We were participants in a dog show, prancing for medals.

Now, 10 years later, polarized Nevadans claw at each other to prove that the other side doesn’t have the right information, destroying friendships and the fabric of our polity in the process. We live in Ralston’s world, where we presume there is an inside to which a wise person must gain access in order to have anything to understand or to say. This is the antithesis of a democratic, free, and equal society. In truth, Ralston’s purported “inside” only consists of one person: Ralston himself.

It’s a pity. Carson City deserves a press corps of as many outsiders as possible, not Ralston’s self-appointed club of lobbyists, aides, pols and “insiders.” And Nevada deserves a Carson City they feel capable of comprehending, if not now then someday. Instead, we get one whose journalistic don, in order to raise his own status, purposely makes it incomprehensible.

If you are part of a society, then you are a part of its politics. And the point at which politics becomes hard to understand is the point at which it is no longer politics but just competitive play, a Risk-style board game. Once there is only a handful of self-qualified players, we no longer qualify as a democracy, or perhaps even a polity.

Jon Ralston plays that game. The thing is, every night, as he clears the pieces off the table to start afresh, Nevada suffers.

Facebook

Twitter

Pinterest

RSS