(Mytheos Holt) – This past week, the New Hampshire Supreme Court struck a welcome blow for free speech, and against frivolous lawsuits.

That opinion came in a case brought by the notoriously litigious firm ATL, which claimed (incredibly) that labeling them a patent troll was legal defamation, rather than a statement of opinion. Their argument effectively boiled down to the idea that an opinion was only an opinion when it was labeled as such: in other words, unless a writer said “I think” or “it is my opinion that” before making a statement, it could be construed as a statement of fact, and therefore was defamatory.

It doesn’t take a genius to spot the logical hole in this absurd misreading of libel law, and the New Hampshire Supreme Court was quick to spot it, and point it out. They noted, for instance, that the term “patent troll” was not a term with clearly defined parameters, but was rather a subjective assessment of a firm’s legal practice, and therefore clearly opinion, rather than a maliciously false statement of fact. There was no way, in other words, to “objectively verify” whether someone was a patent troll. Moreover, it was obvious that simply saying “I think” before a statement didn’t mean it couldn’t be defamatory. “It is my opinion that ATL’s founder flew on Jeffrey Epstein’s Lolita Express more often than Bill Clinton” would, for instance, obviously be a defamatory statement. Though, as the kids say, “big if true.”

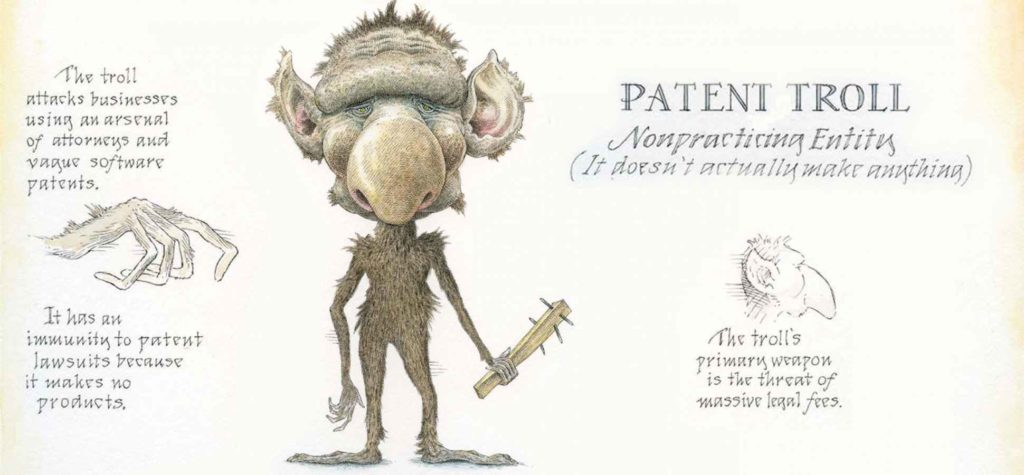

Now, for anyone who knows what a patent troll is supposed to be – a rent-seeking firm that relies on frivolous patent infringement lawsuits in order to extort money from actual inventors – the idea that a firm associated with the practice would rely on specious legal arguments is a “dog bites man” level story. As is the fact that they lost. Libel suit trolling isn’t nearly so easy, or so profitable, as patent trolling. Nevertheless, the incident bears remarking upon because it relates so obviously to yet another attempt by the patent troll lobby to throw out longstanding, commonsensical legal precedent by rewriting the law to favor their interests.

That attempt comes in the form of legislation by Sens. Thoms Tillis (R-NC) and Chris Coons (D-DE) to rewrite the over 100-year-old definition of what constitutes a “useful” invention to permit everything up to and including natural phenomena to be patentable, while also junking longstanding limits on the ability of, say, pharmaceutical companies to extend their monopoly rights over certain drugs in perpetuity. In other words, it’s crony capitalism masked in the guise of legal reform, and a boon to some of the least popular, and least public-spirited industries in the country.

The only purpose of this bill, and it’s one that its proponents are at least honest enough to admit to, is to overturn the Supreme Court’s ruling in Alice Corp v. CLS Bank International, a unanimous decision written by none other than Justice Clarence Thomas, which held that a “patent” for a computer performing settlement risk (note: not a specific program, just the concept of doing this on a computer) was invalid because it attempted to patent an abstract idea. This cut into the trial bar’s profits, and so they have been trying, so far with mercifully limited success, to get Alice overturned in Congress. Sadly, they have been aided in this effort by more than a few misguided conservatives, who somehow are under the impression that Clarence Thomas deliberately wrote a Supreme Court decision with the intention of undermining property rights.

At the risk of avoiding defamation lawsuits by ATL, let me put this in terms even they will recognize as opinion – albeit well-founded opinion. It is my very, very well-considered opinion that this effort is one of the most transparent attempts to legally enshrine intellectual property oligarchy in recent memory. I think that the firms who support this effort – ATL no doubt among them – are maliciously twisting the meaning of words in order to not have to earn their bread. I feel that rent-seeking garbage institutions and their rent-seeking cronies in Congress should learn that words mean things – you know, words like “defamation,” “opinion,” and “useful.” And if they don’t like what those words mean, I feel they should consider that it’s not defamatory to hold the same opinion as the American people: that folks who try to change the rules when they lose are most certainly not useful.

I suspect that others hold the same opinions. I only hope that they prevail in Congress.

Mytheos Holt is Senior Fellow in Freedom to Innovate at the Institute for Liberty. This column was originally published by Town Hall on September 9, 2019

Facebook

Twitter

Pinterest

RSS